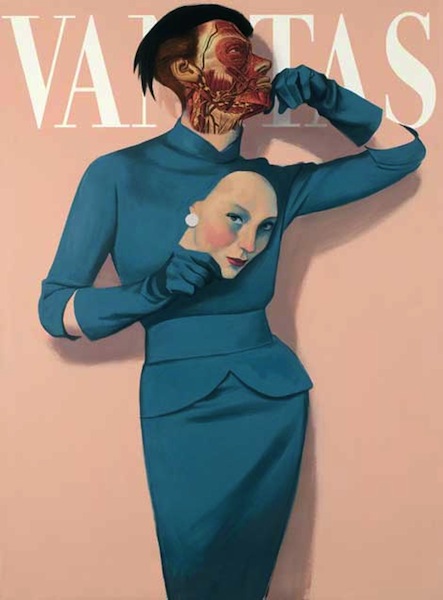

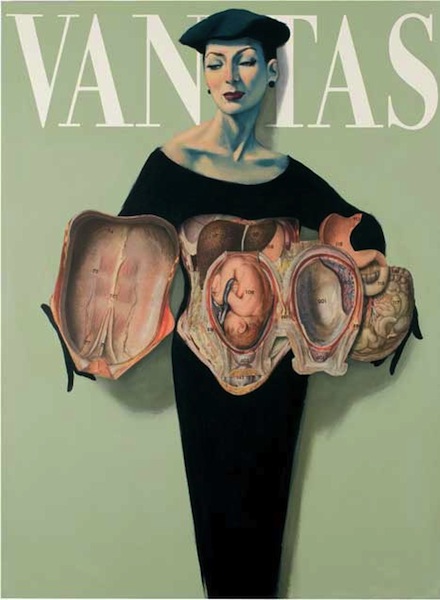

Fernando Vicente “Vanitas” (2008)

“For a long time, the inside of the human body has been reserved for the exclusive use of medicine and science. It is time to claim it for our own contemplation.”

Thus does Fernando Vicente summarize the concept behind his Vanitas series, an introspective modern take on the recurrent theme of vanity in the history of painting, where the icon-making fashion machine fails to immortalize its hepburnesque subjects. His models, oblivious to their own exposure, tantalisingly reveal muscles, tendons, viscera and bones, presenting us with a difficult yet disturbingly enticing experience.

Rather than skin deep, the anatomical sections seem superimposed on the figures in the manner of jewelry or tattoos, transforming body parts into statement fashion accessories, their red, pink and yellow palettes starkly contrasting with the demure poise of the models and sober background. Their message, simple yet crushing, reminds us that despite the layers of sophistication that affluence and class afford, we are all flesh and bone underneath. Moreover, it proposes a most exuberant and interesting kind of beauty residing beneath all artifice, away from imposed aesthetic canons.

By offering glimpses of the complex inner reality of the female body, Vicente incisively comments on fashion’s zeal for its objectification and containment, which presents a deceptively sophisticated version of womanhood, sanitized, depthless, purely ornamental. Although vulnerably exposed to the prying eye, these twentieth century anatomical venuses comply with nothing of the sort, they are raw, unpleasantly explicit, almost obscenely dissected to expose, by virtue of contrasts, their own multifaceted complexity.

Most accordingly, the artist’s selection of 1950’s conservative tailoring and noir siren looks further expands on characterisation, theatricality and restraint, essential traits in the fashion world, where women are paradoxically allowed to express their “individuality” and coaxed to do so within a highly regimented yet flamboyantly creative framework. The result being an eerie homogeneity, where all women become mirror images of one another by striving for authenticity behind an elaborate smokescreen.

On the contrary, Vicente’s women acquire depth and individuality through undressing their inner yearnings, which exposed entrails embody: consuming passion, motherhood, sensuality, deep reflection. His scalpel-sharp pen exquisitely captures the intricacy of medical art, masterfully grafted on to film and fashion photography to produce a startlingly exciting hybrid specimen of beauty, paradoxically delicate and brutal, flirtatiously daring and stunningly honest.

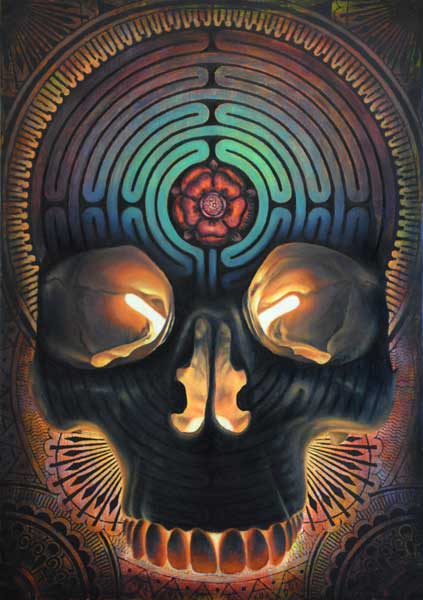

Equally captivating are his Anatomías and Venus series, the first being an exploration of the body as machine and the second a reinterpretation of classical feminine beauty in a contemporary alternative framework.